Human motivation is a moving continuum

A question on every parent’s mind is, “how do I motivate my child to do what is good?”

Self-Determination Theory, or SDT, uses scientific methods to explore factors that both enhance and detract from human motivation.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Many parents have heard about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, but let’s define them.

Intrinsic motivation is when a person wants to do a task purely for the pleasure of it. The reward is in the doing, so to speak, and not tied to anything outside the person’s own curiosity and interest.

Extrinsic motivation is when a person wants to do a task because of a perceived reward or punishment. It could be direct, like a promise of a cookie upon completion, or it might be anticipation that completion will increase social status. The defining element is that the person does the task “in order to [fill in the blank].”

Parents with young children may marvel how intrinsically motivated our little ones are to learn and explore, but when it’s time for our child to eat their dinner we resort to coercion. We know that internal motivation is ultimately what we’re after, for we don’t want them to eat vegetables only because we’ll give them a treat afterward, but we default to what works. A clear understanding of how people internalize motives is a considerable benefit to parents.

The Motivation Continuum

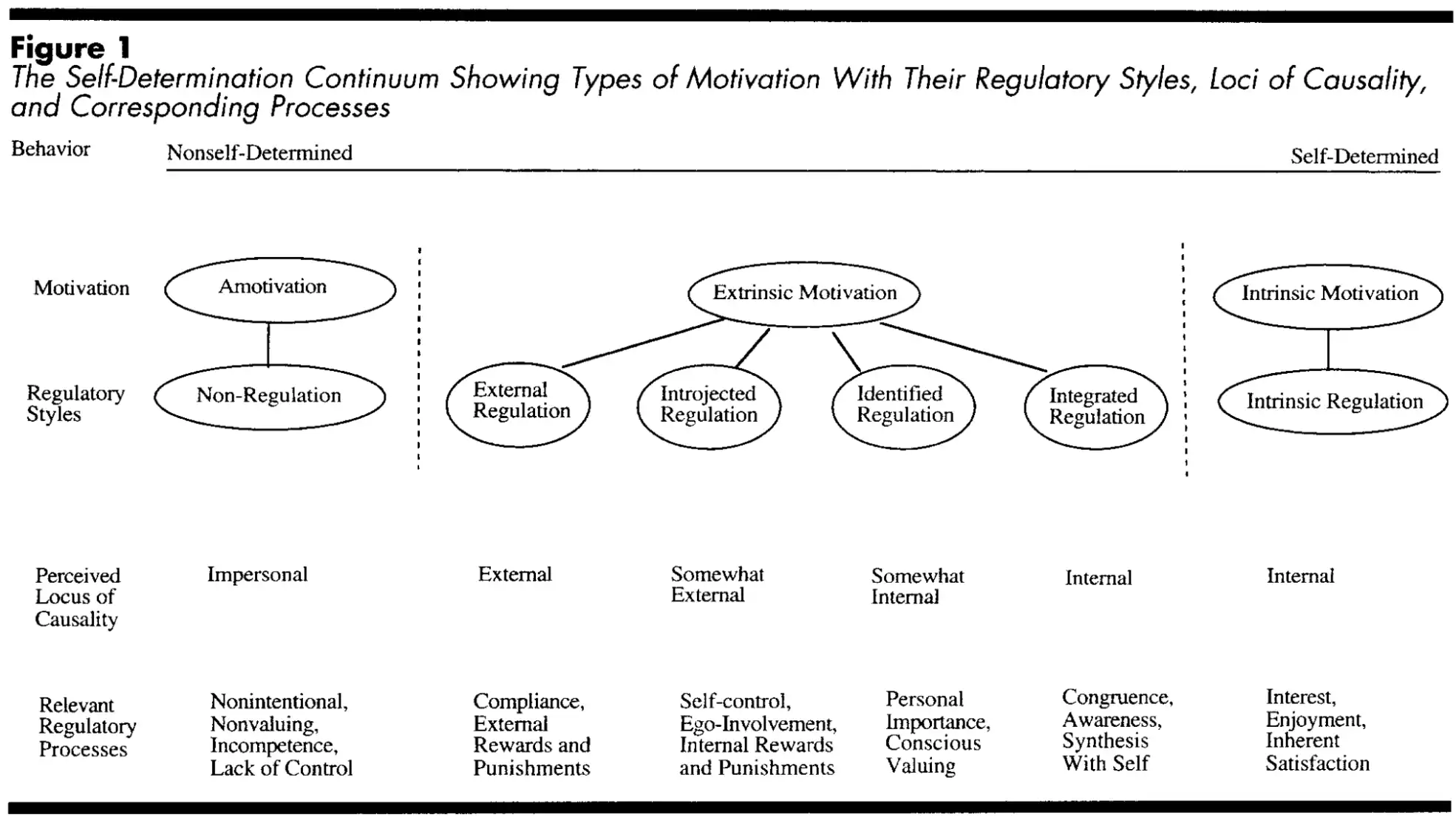

Deci and Ryan concluded in 1985 that motivation should be defined with more granularity than only two options, internal and external. A 1989 study by Ryan and Connell validated that school children will move from purely extrinsic motivation towards intrinsic in a quasi-simplex pattern. In layman’s terms, they tested student’s motivation in key areas over a time frame and found that there was steady movement from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation until their motivation eventually reached a plateau. With these findings Deci and Ryan composed the following diagram.

To explore the degrees of regulation marked in their continuum, let’s consider an elementary school student named Johnny who is faced with math homework after school.

Johnny’s Example

If Johnny has amotivation, or is non-regulated, he’s not going to do the homework. Period.

If Johnny is externally regulated, he may comply to doing the homework, but only because you promised him cake afterward. Or maybe you warned him that he’ll lose his favorite privilege.

If Johnny has introjected regulation, he might remember the pride he felt at the last parent-teacher conference when his teacher told you he’s “very bright,” and wants to keep that reputation. Or he might feel shame because he’s struggling in math and wants to prove his intelligence and persistence.

If Johnny has identified regulation, he imagines how this homework will move him a step closer to his personal goal of becoming a zoologist. Or he may think of the people he’s met who didn’t graduate from school and engage his homework out of a conviction that he won’t be like them.

If Johnny is internally regulated, he jumps on his homework because that’s what he is, a student who completes his homework. He may daydream about becoming a zoologist, but even if that goal changes he’ll still do his homework. Outwardly, his motives are impossible to distinguish from intrinsic motivation. They’re not classified as intrinsic only because their origin lies in external factors and not pure enjoyment.

Finally, if Johnny is intrinsically motivated he does his homework because it’s the most pleasurable activity he can do right now. He LOVES winning at math.

Factors that Affect Motive Internalization

From Deci, Ryan and Connell’s studies there is evidence that people will move from external regulation towards internal regulation. However, movement along this continuum is not guaranteed. Deci and Ryan underscore three interrelated categories which summarize the results of a host of studies: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When each of these three categories is supported, a person’s motive internalization is enhanced. Where they are hindered, however, a person’s internalization is diminished or even halted.

Autonomy

The degree in which a person experiences autonomy determines whether the task will enhance their intrinsic motivation or undermine it. When external control is exercised, irregardless of whether it’s reward or punishment, the person’s sense of autonomy is diminished and the potential for intrinsic growth is minimized.

It’s important to note that autonomy does not equate to a person’s ability to do a task without help. Autonomous action is based only on the perception that it was the person’s private choice to engage in the task and not sourced by outside pressure.

💬

autonomy refers not to being independent, detached, or selfish but rather to the feeling of volition that can accompany any act, whether dependent or independent, collectivist or individualist.

Deci & Ryan (2000), pg. 74

Competence

When a person is capable of achieving a task, they are competent. Incompetence arises when a task is beyond their developmental capacity, as when a three-year-old is pressured to calm themselves down, or their internal resources, as when additional demands are placed on an already physically and emotionally burnt-out mother.

While Deci and Ryan do not explicitly state this, I think competence also requires a measure of challenge. An effortless task that a person is over-qualified for is often a demotivating factor. Whether it diminishes a person’s internalization, I don’t know for sure, but it’s worth noting.

Relatedness

Relatedness is a bit fuzzy, but essentially refers to the support lent to a person from others to whom they have a positive attachment. This can directly facilitate motivation, such as when an elementary school student relates to an adult whom they seek to emulate. But it does not have to be direct. Strong attachments facilitate motivation in unrelated tasks by supplying a general sense of security and well-being. Likewise, relational conflict or isolation has negatively affects motivation, even where tasks which are not directly associated.

Motivation and Well-Being

A person with a high degree of autonomy, competence and relatedness experiences their activities with a sense of accomplishment and well-being. When others hinder any of these conditions, they not only undermine the person’s motive internalization, they also diminish their well-being.

💬

We maintain that by failing to provide supports for competence, autonomy, and relatedness, not only of children but also of students, employees, patients, and athletes, socializing agents and organizations contribute to alienation and ill-being.

Deci & Ryan (2000) pg. 74

Conclusion

Human motivation for any task lands on a continuum with multiple degrees of internalization. Steady movement from external motivations towards internal depends on the conditions of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When there are positive conditions, well-being is maximized. Hindrances to those conditions, however, undermine motivation and damage well-being.

Parents who seek the highest well-being of their children and to equip them to do good apart from external pressures will therefore pay special attention to their child’s autonomy, competence, and relatedness conditions. They will ask whether their children is given opportunity to choose for themselves, or if their behavior is solely based on external rewards or punishments. They will consider the developmental stage of their children and the tools at their child’s disposal to ensure that they have everything necessary to complete the task. Finally, they will emphasize an unconditioned relationship with their children and assist them in the healthy navigation of interpersonal conflict.

References

- Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627-668.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist. pg 72.

- Eisenberger, R., & Cameron, J. (1996). Detrimental effects of reward: Reality of myth? American Psychologist, 51, 1153-1166.

- Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749-761.